Top Class Actions’s website and social media posts use affiliate links. If you make a purchase using such links, we may receive a commission, but it will not result in any additional charges to you. Please review our Affiliate Link Disclosure for more information.

The federal government signed an agreement with the Assembly of First Nations last week regarding federal funding of the First Nations child welfare system — an important detail that was left out of Trudeau’s Bill C-92. The new agreement gives substance to Aboriginal rights and adds to Bill C-92, which aims to reduce the number of Aboriginal youth in care and allows First Nations communities to create their own child welfare systems.

This new agreement is at the least overdue, given Canada’s past and current record of Aboriginal youth overrepresentation in the child welfare system. In fact, earlier this year, the Assembly of First Nations filed a $10 billion class action lawsuit accusing the Canadian government of underfunding the First Nations child welfare system in the Yukon and on reserves. The class action claimed that Canada’s child welfare system discriminated against First Nations children.

The Assembly of First Nations’ class action lawsuit brought to light Canada’s systemic discrimination against Aboriginal communities, through discriminatory funding that incentivized the removal of First Nations children from their families.

Another recent lawsuit, echoing previous discrimination claims, was brought by a First Nations woman against Manitoba’s child and family services agencies after three of her children were apprehended by provincial child services in 2007. The mother spent years trying to recover her children, who were allegedly abused in foster homes.

The new federal agreement is anticipated to address Canada’s systemic issues with regards to discrimination against Aboriginal communities across the country. Indeed, First Nations youth are currently overrepresented in the child welfare system, however, Canada also harbours a dark history of discrimination and abuse toward Indigenous children, one that can be traced to Canada’s residential and federal day school systems.

The agreement between the federal government and the Assembly of First Nations not only represents an attempt at remedying past discrimination, but it also raises First Nations constitutionally protected rights — rights that are meant to prevent the discrimination and abuse riddling Canadian history.

Aboriginal Rights

Aboriginal rights are collective rights that flow from Aboriginal peoples’ continued use and occupation of certain areas dating from before European contact. Although these specific rights may vary between Aboriginal communities, they generally include rights to the land, rights to subsistence resources and activities, the right to self-determination and self-government, and the right to practice their own culture and customs including language and religion.

In 1982 the federal government enshrined Aboriginal rights in Section 35 of the Canadian Constitution and in Section 25 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

Section 35(1): Inherent Aboriginal Rights

Section 35(1) provides Constitutional recognition of inherent Aboriginal rights, treaties and treaty rights. It recognizes that First Nations have inherent sovereignty, inherent rights and the power of self-determination. Inherent rights refer to rights stemming naturally, rather than granted by government, and include:

- Inherent rights to language, spirituality and culture;

- Inherent rights of education, social and health;

- Inherent rights to justice and economics;

- Inherent rights to citizenship/citizens and membership;

- Inherent rights for fishing, hunting, trapping and gathering;

- Inherent rights to air and water;

- Inherent rights to lands and resources; and

- Inherent rights and powers to self-determination.

Section 35(1) and (2) expand upon federal legal, political and fiscal obligations under section 91(24) of the British North America Act 1867. This means that the federal government and Parliament are obligated to legally uphold inherent Aboriginal rights.

Section 35(2): Recognition of Indian, Inuit and Métis Peoples

Section 35(2) of the Constitution Act 1982 constitutionally recognizes Canada’s various First Nations peoples. Additionally, it provides citizenship recognition in the form of dual Canadian citizenship for Aboriginals. More broadly, section 35(2) establishes a legal and political framework that recognizes the formal government-to-government bilateral relations between the Crown and Aboriginal governments.

Section 25: Safeguarding Aboriginal Rights

Various Supreme Court decisions discussed the purpose of section 25. Some decisions declared section 25 a mechanism for the reconciliation of conflicts between the rights and freedoms guaranteed by the Charter and rights and freedoms of the Aboriginal peoples of Canada. Additionally, the plain wording of section 25 has led the Court to rule that it does not create new rights, but rather, protects against the abrogation or derogation of existing Aboriginal, treaty or other rights or freedoms via Charter protections.

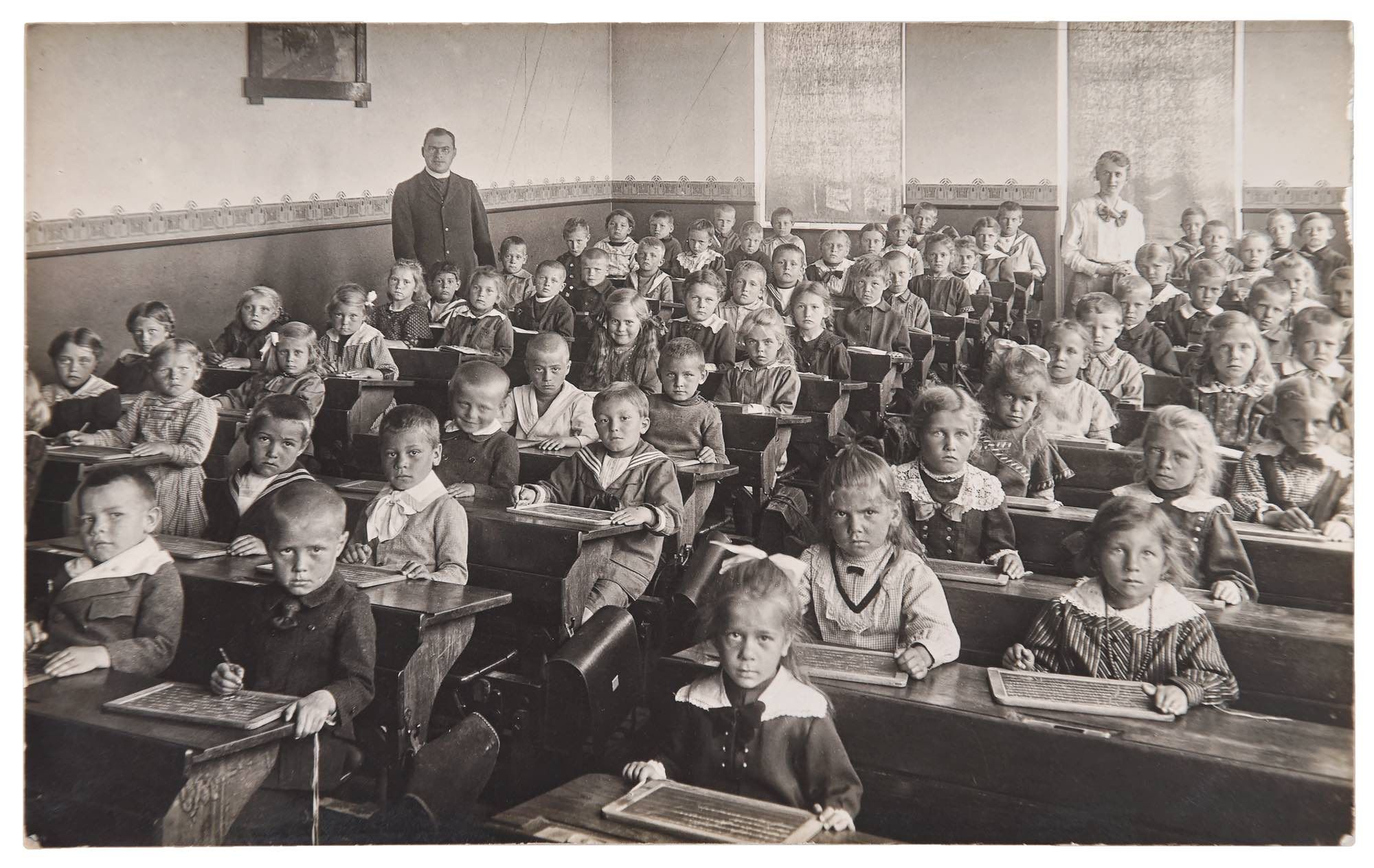

Canada’s Residential Schools

Canada’s history of discrimination toward Aboriginal youth is most evidently illustrated through the country’s residential schools. The first residential facilities were developed in New France by Catholic missionaries, and were intended to provide care to Aboriginal children. At this time, however, the colonial French government did not force Indigenous people to participate in the schools, as First Nations were largely independent and the French settlers depended on them economically and militarily.

Residential schools began to change in the 1830s, when they became part of government and church policy, with the creation of Anglican, Methodist, and Roman Catholic institutions in Upper Canada.

Aboriginal leaders hoped Euro-Canadian schooling would help their youth learn new skills and support their transition to a world dominated by strangers. With the passage of the British North America Act in 1867, and the implementation of the Indian Act, the government was required to provide Aboriginal youth with an education and to assimilate them into Canadian society. Contrary to the hopes of First Nations communities, the federal government supported schooling to decrease Indigenous dependence on public funds. The objectives of the government and First Nations diverged, and residential schools took on a sinister face, as the federal government collaborated with Christian missionaries to encourage religious conversion.

This eventually led to the development of an educational policy after 1880 that relied heavily on federal residential and day schools.

The Canadian government developed a policy known as “aggressive assimilation” to be taught at church-run, government-funded residential schools. The reason behind “aggressive assimilation” was the belief that Canada’s Aboriginal population was easier to mold as children than as adults. As such, the concept of a “boarding school” was considered the ideal way to prepare Indigenous youth for life in mainstream Canadian society.

Residential schools were federally run, under the Department of Indian Affairs. Attendance at residential schools was mandatory for children in communities that didn’t have Federal Indian Day Schools. Agents were employed by the government to ensure all First Nations children attended federal residential or day schools.

It is estimated that about 1,100 students attended 69 federal schools across the country beginning the 1880s. In 1931, at the peak of the residential school system, there were approximately 80 residential schools in Canada. In all, about 150,000 First Nation, Inuit and Métis children were removed from their communities and homes and forced to attend federal schools.

Abuse in Residential and Day Schools

Residential and Federal Day Schools were established with the assumption Aboriginal culture could not to adapt to Canadian society. The government believed that First Nations children could be successful if they assimilated into mainstream Canadian society by adopting Christianity and speaking English or French. Therefore, students were discouraged from speaking their native language or practicing native traditions. If caught violating these harsh and discriminatory rules, they would be subjected to severe punishment.

Students in residential schools lived in substandard conditions and endured physical and emotional abuse. In recent years, there have been several convictions of residential school personnel for sexual abuse charges.

Indigenous children attending residential schools were forcefully estranged from their families, most of whom were in school 10 months a year. Some students even stayed year round. Another form of estrangement for Aboriginal youth in federal schools was their requirement to write all correspondence to their family in English, which meant that most parents couldn’t read or understand their child’s letters.

Additional abuse that was only recently revealed came in the form of nutritional experiments that were conducted in certain residential schools. These experiments were carried out on malnourished students in the 1940s and 1950s under the federal government’s approval.

The negative affects of residential and day schools lingered on Canada’s First Nations in various ways. When students returned home, they often found they didn’t belong. Students lacked the skills to help their parents, and many became ashamed of their heritage. Furthermore, the skills taught at the schools were largely substandard, and many had great difficulty functioning in an urban setting.

In 2007, the federal government implemented the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement. The settlement agreement was reached between legal counsel for former students, legal counsel for the Churches, the Assembly of First Nations, other Indigenous organizations and the Government of Canada. It aimed to bring a fair and lasting resolution to the legacy of Indian Residential Schools in Canada.

Over a decade later, in March 2019, former Indian Federal Day School students reached a class action settlement with the federal government that would compensate survivors for the abuses they suffered while attending the federally operated schools.

What do you think about the new agreement the federal government signed with the Assembly of First Nations? Tell us your thoughts in the comment section below!

ATTORNEY ADVERTISING

Top Class Actions is a Proud Member of the American Bar Association

LEGAL INFORMATION IS NOT LEGAL ADVICE

Top Class Actions Legal Statement

©2008 – 2024 Top Class Actions® LLC

Various Trademarks held by their respective owners

This website is not intended for viewing or usage by European Union citizens.